Nude:Theory

edited by Jain Kelly and published in 1979 by Lustrum Press

Nude:Theory is a collection of articles and photographs by eight photographers: Manuel Alvarez Bravo, Harry Callahan, Lucien Clergue, Ralph Gibson, Kenneth Josephson, André Kertész, Duane Michals, and Helmut Newton. No women photographers were included, and only Duane Michals' article includes nude photographs of men. Make of this what you will.

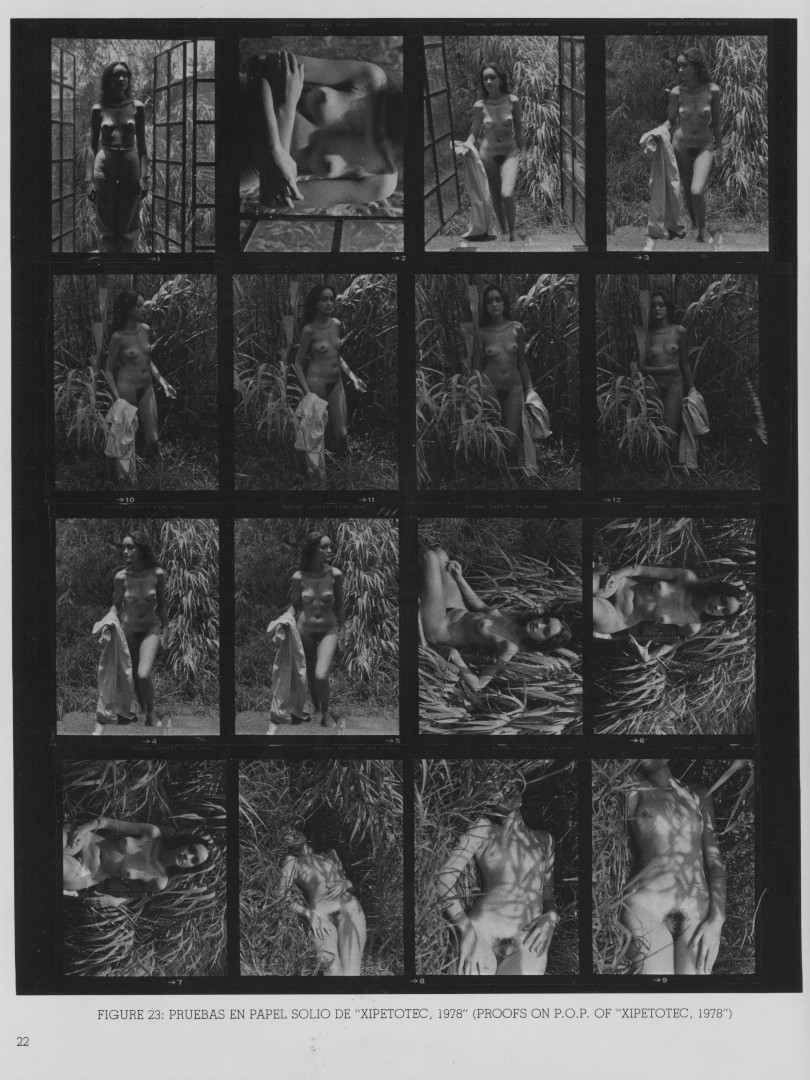

Each article presents a series of photographs and contact sheets alongside an article that covers the photographers' philosophical approaches to photography and/or nude photography, a discussion of the included photographs, and sometimes technical information about how the photos were made, developed, and printed.

In my experience, finding information about the techniques of noteworthy photographers is difficult, so if that's your area of interest, this book is for you. Having only dabbled in film photography decades ago, I found the bits related to film development to be of historical interest only.

I much preferred the discussion of the ideas of the photographers and how they played out in the included photographs. For me, the most interesting articles were those by Manuel Alvarez Bravo (in-depth and thought provoking), André Kertész (amusing and direct), and Duane Michals (insightful thought processes behind the images). Your mileage may vary.

I'll include some quotes and outlines of technique from each photographer that struck my fancy.

Manuel Alvarez Bravo: "People are very curious. They always ask the artist why he made something and what it means. They should hold discourse with the work of art itself, and perhaps it would say something different to them than its author would indicate. This would signify that the work has a richness and can express itself by itself. It is not necessary that it be explained; it's only necessity is to exist. ... When I am asked about it, I say, 'Well, because I liked it.'... But the 'why' remains. Perhaps the importance of these questions is that the author, the creator of the work of art, may come to realize himself what he wanted to do. He may find another meaning in his own work."

Bravo used many cameras throughout his career, including a 6x9 cm Plaubel camera with an Anticomar f/4.2 lens and a Hasselblad 2 1/4" x 1 5/8" camera with a variety of lenses. Films used include Kodak Tri-X and Plus-X, and he printed on Agfa and Kodak papers. Bravo provides the most detail about his film development processes of all the photographers. He includes Tina Modotti's developer and fixing bath formulae for platinum prints, of which he says "[It] is very strange, very different from what we use now, and I have not tried it lately."

- Developer:

- - Water, 43 oz

- - Sodium citrate, 10 oz

- - Citric acid, 1 oz

- Fixing Bath:

- - Water, 150 oz

- - Socium citrate, 5 oz

- - Citric acid, 2 ox.

- Temperature

- - 45-60 F

André Kertész: "In each country in which I have lived, I have used the atmosphere of the country itself in my photography. ... I used the atmosphere, but I didn't push myself into anything. I never tried to analyze or speculate on what I was doing. ... [In the] United States ... the atmosphere was less warm than in Paris or Hungary, and the times were difficult. ... The photographs I make today in New York can never be as warm as the ones I made in Paris in the 30s. ... The people are different, even the streets are constructed differently. In Paris, everyone is an individual; here are only the masses. I do not pass judegement on this. It is simply that life here is different. It is important to comment on this, because the photographer's experiences and feelings dictate the way he sees."

Kertész started out with a box camera that took glass plates. The camera had "only one shutter speed, so I could not always be sure how my pictures would come out. It was very primitive." He said he made small images with small cameras, "'Leica pictures' long before there was such a thing as a Leica." He began to use larger images when his brother gave him a 9x12 cm glass plate Voigtlander camera.

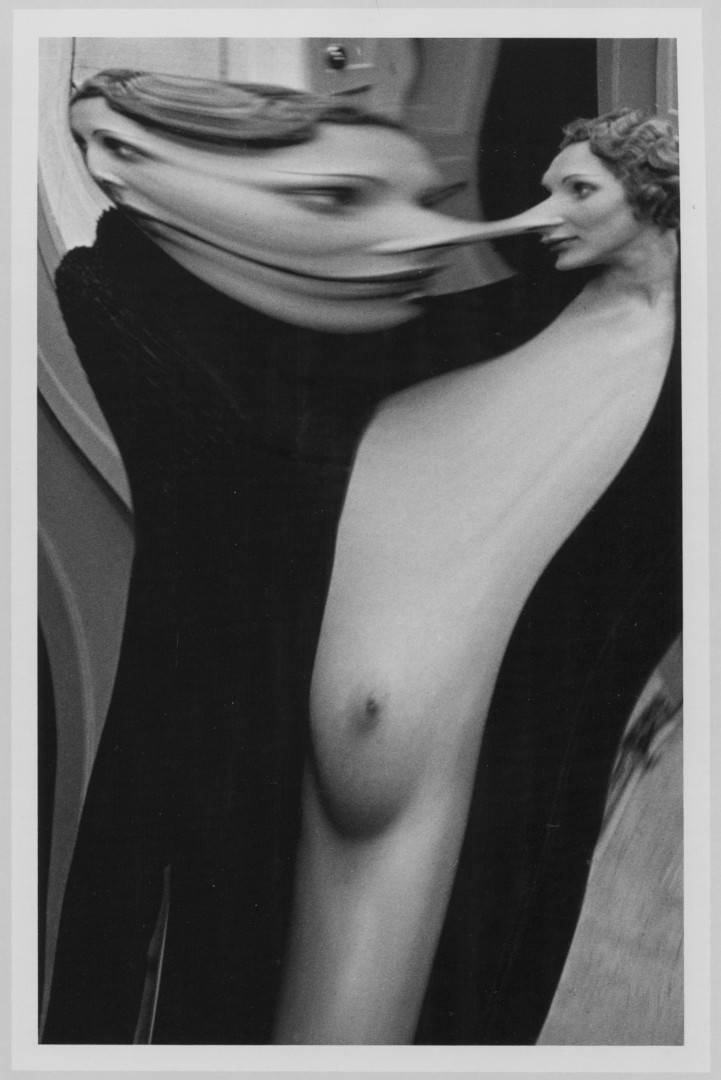

He also used a non-interchangeable lens Leica with an Elmar 50mm f/3.5, but struggled to capture his distorted nudes with it. He achieved his vision with a 9x12 cm glass plate Linhof camera with Hugo Meyer Plasmat Satz lenses, "combination lenses that were forerunners of the zoom lens." These lenses could be used individually or stacked to achieve various focal lengths. Even using this more flexible solution, he was still obliged to print crops for about 20% his distorted nudes.

I learned an interesting word from Kertész's article: witziger. "My belief is that a photographer should avoid a complicated approach and express his own feelings. There is a charming story that took place in Paris in the 1930s. The people from the Bauhaus used to visit me when they came to Paris. I remember that one visitor ... told me, 'You are not "Witziger" enough.' Witziger means that when you have an itch, you scratch around it first, instead of going directly to it with your hand. He meant my work was not indirect enough, not amusingly complicated enough." This was a view Kertész disagreed with: "I feel that a photographer should try to be as direct as his eye sees, without a lot of ridiculous playing around. ... if something is interesting, then it is interesting; if it's not, then there is no reason to force it to be interesting."

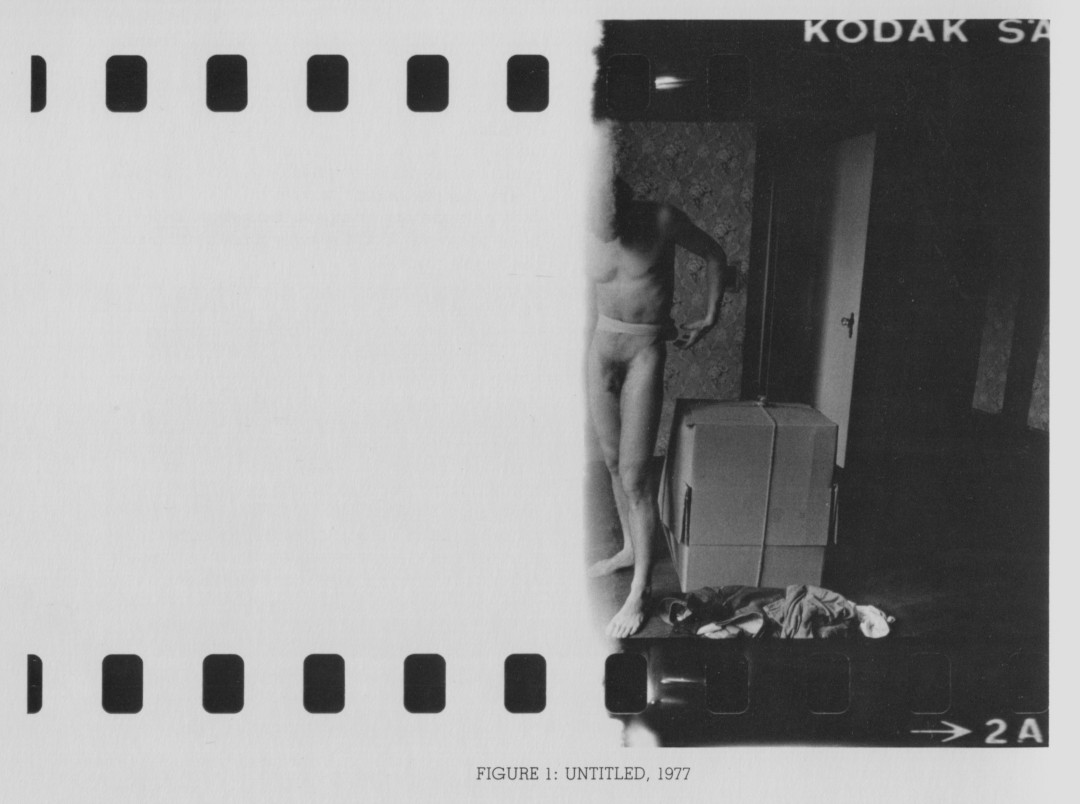

Duane Michals: "As far as the sexual aspect of the nude is concerned, there is no such thing as an innocent nude, even a photograph of a 97-year-old person. The viewer still responds out of a sexual curiosity. In the case of the old person, there is always the sense of physical loss. ... One of the things a photographer should talk about is the pleasure it gives him to photograph the nude. No one can tell me that the photographer of the nude doesn't enjoy his work. There is a pleasure in looking at the body, being aware of the presence of the body, of working with the choreography of the figure in motion. It is even possible to make an ugly body beautiful, merely by finding the right angle."

Michals shot with a Nikon 35mm, and frequently used a 35mm lens, with which he could "include both the figure and the room with relatively little distortion." He goes on to say, however, that "the mechanics of photography should never get in the way of making the photographs." He used only Kodak Tri-X rated at 400 ASA with a Brockway incident light meter, and preferred "soft, natural, window light". At the time of writing, he was beginning to experiment with painting on his prints to further develop his ideas.

Recommended

Reviewed 2024-02-29